Renuka Mopuru, MD, Paulina Liberman, MD, and Amde Selassie Shifera, MD, PhD

Abstract

In this case report, we describe a 12-year old Caucasian boy with pre-existing bilateral idiopathic uveitis who presented with a sudden onset ciliary body mass in his right eye associated with a flare-up of his intraocular inflammation. He was treated with topical prednisolone and oral prednisone, which controlled the intraocular inflammation while also resulting in a rapid resolution of the ciliary body mass without recurrence at a one-year follow-up. The prompt resolution of the ciliary body mass and the absence of recurrence indicated that the mass was an inflammatory lesion associated with his uveitis.

Case Report

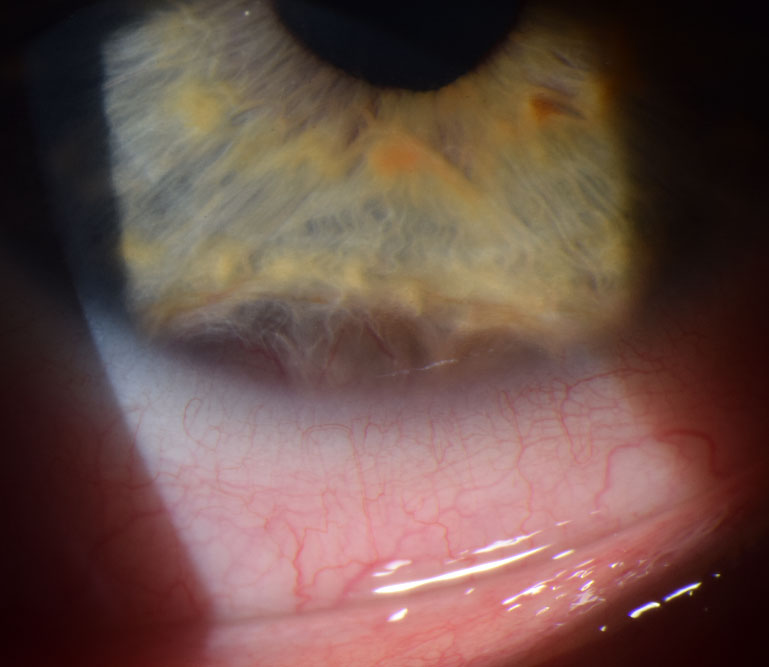

A 12-year old Caucasian boy presented to our tertiary care facility for evaluation of bilateral uveitis. Seventeen months before presentation, the patient developed sudden onset of pain and redness involving the right eye. An ophthalmologist evaluated him three weeks after the onset of his symptoms and he was found to have inflammation in the anterior chamber of the right eye. Six weeks after the onset of his symptoms he was found to have inflammation in the anterior chamber of the left eye also, vitreous cells in both eyes, a serous retinal detachment involving the macula of the right eye (Figure 1) and edema of the right optic disc. Before his presentation to our clinic, the patient had been having recurrent flare-ups of his uveitis for which he required courses of topical 1% prednisolone acetate or 0.05% difluprednate drops; he had also been on long-term oral prednisone. In addition to his ocular symptoms, the patient also reported having red bumps on the lower legs that occurred during the summer months for the two years preceding his presentation to us.

At his initial presentation to our clinic his corrected visual acuity was 20/30 in each eye. His IOP was 14 mmHg in each eye. He had trace fine keratic precipitates, 2+ anterior chamber cells, 1+ flare, a focal posterior synechiae, 1+ posterior subcapsular cataract and 1+ vitreous cells in the right eye and trace fine keratic precipitates, 1+ anterior chamber cells, 1+ flare, trace posterior subcapsular cataract and old vitreous cells in the left eye. His fundus examination was non-remarkable, but three months after initial presentation, a few punctate atrophic spots inferiorly in the fundus of the right eye were noted. A uveitis work-up was non-remarkable, including negative serology for Lyme disease and for syphilis, negative Quantiferon TB Gold (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), normal urinalysis, normal urine β2-microglobulin, a negative test for HLA-B27 and a normal chest X-ray.

His past medical history was significant for a history of viral meningitis during his infancy, history of Pseudomonas spp. bacteremia with an associated secondary Sweet syndrome during the second year of his life, a history of influenza A pneumonia with atelectasis of the left lower lobe during the third year of his life, a history of recurrent otitis media and a history of atopic dermatitis. In light of his repeated infections, the patient had an extensive work-up for immunodeficiency but the investigations were non-remarkable.

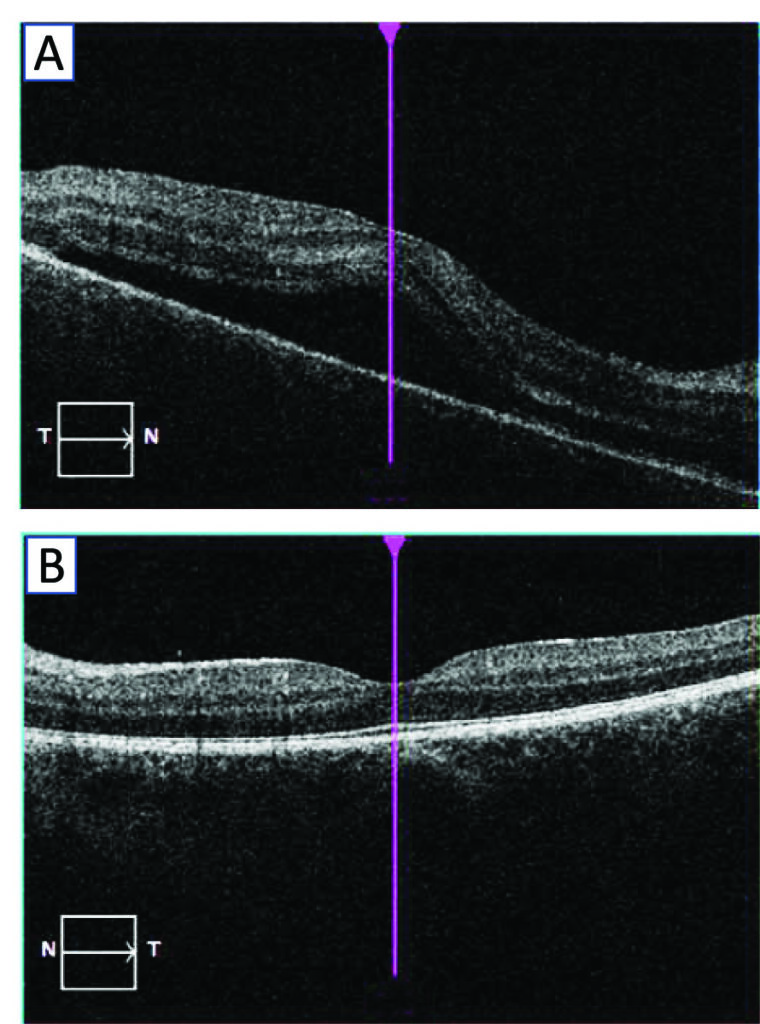

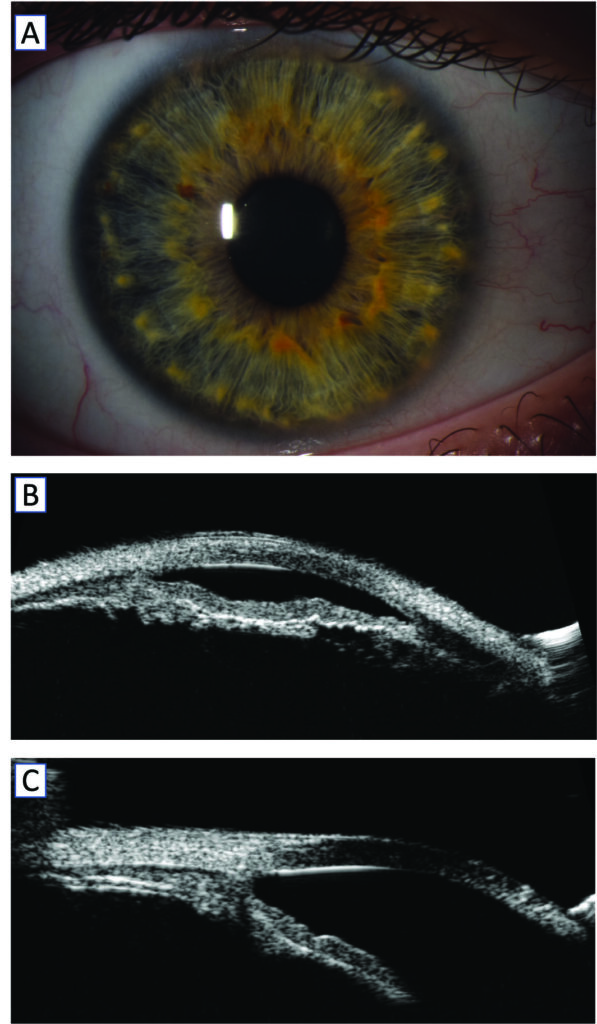

He was on prednisone 4 mg daily and on difluprednate BID OU at the time of his initial presentation to us. He was weaned off the oral prednisone and was continued on topical difluprednate which was later switched to topical prednisolone. Five months after his initial presentation to us, the patient returned with a marked flare-up of his uveitis, having fine keratic precipitates OU, 3+ anterior chamber cells OU, 2+ flare OD and 1+ flare OS. During that flare-up he was also noted to have vitreous cells and vitreous haze in both eyes. At the same time, he was noted to have an oval-shaped circumferential nodule displacing the inferior iris anteriorly with the vessels in the overlying iris engorged (Figure 2, A, B and C). A 50 MHz ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) showed a highly reflective lesion inferiorly involving the pars plicata portion of the ciliary body (Figure 2 D, E and F). The lesion had a maximal thickness measuring 2.3 mm with the basal diameter measuring 6.2 mm laterally and 2.7 mm radially.

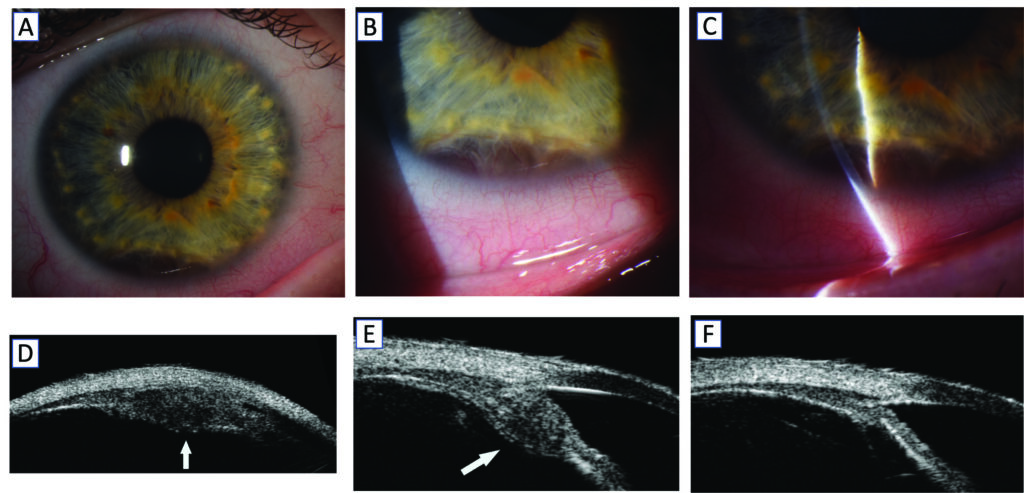

The patient was started on a course of oral prednisone and the dose of his topical prednisolone was escalated. He was also started on oral methotrexate for long-term immunosuppression. After approximately four weeks on oral prednisone clinically the nodule appeared resolved as depicted on a slit lamp photograph and also as evidenced on UBM scans taken two months after presentation with the ciliary body mass (Figure 3).

The patient was able to taper off the oral prednisone after three months. At his last visit, one year after the onset of the ciliary body mass, his corrected visual acuity was 20/30 OD and 20/30 OS. He was on oral methotrexate 20 mg and on topical 1% prednisolone acetate TID OU with no active inflammation in both eyes and no clinical recurrence of the ciliary body mass in the right eye.

Discussion

The patient presented here had panuveitis of the right eye and anterior and intermediate uveitis of the left eye before developing an acute onset ciliary body mass in the right eye. The work-up for common infectious diseases was negative, and the review of systems and laboratory testing did not show evidence of systemic disease. The timing of appearance of the ciliary body mass during an acute flare-up of his uveitis was highly suggestive of an inflammatory origin. The rapid resolution of the mass after steroid treatment also supported the notion of an inflammatory process. The possible differential diagnoses in our patient included childhood sarcoidosis1,2 or the development of a pseudotumor in the presence of active idiopathic intraocular inflammation.3

Although the cause of the uveitis in our patient remains undetermined, sarcoidosis appears of likely because of the presence of punctate atrophic spots in the retina, the development of a presumed inflammatory ciliary body mass and the history of suspected erythema nodosum (suggested by the history of red bumps on the lower legs) which support the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis is rare in children, with one study estimating the incidence to be 0.29/100,000 per year among Danish children.4 Anterior uveitis is the most common ocular manifestation of sarcoidosis in the pediatric age group.5 Granulomatous nodules involving the choroid, optic nerve, conjunctiva, lacrimal gland and iris have been reported in patients with sarcoidosis.6-8 However, ciliary body mass associated with sarcoidosis seems to be rare. To date, there are only 4 cases of biopsy-confirmed ciliary body mass due to sarcoidosis reported in the literature: 1 case reported by Finger et al in 20071 and 3 cases reported by Teo et al in 2020,2 with all of the four cases being adults. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis in children with no systemic manifestation is often presumed. In our case pathological examination was not done due to the highly invasive nature of the procedure in a child for obtaining a specimen for pathological evaluation and to the fact the mass resolved within a few weeks.

References

1. Finger PT, Narayana K, Iacob CE, Samson CM, Latkany P. Giant sarcoid tumor of the iris and ciliary body. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2007;15:121-5.

2. Teo HMT, Elner SG, Sassalos TMP, Elner VM, Demirci H. Ciliary Body Mass as a Feature of Ocular Sarcoidosis. JAMA Ophthalmol 2020;138:300-304.

3. Ryan SJ, Jr., Frank RN, Green WR. Bilateral inflammatory pseudotumors of the ciliary body. Am J Ophthalmol 1971;72:586-91.

4. Hoffmann AL, Milman N, Byg KE. Childhood sarcoidosis in Denmark 1979-1994: incidence, clinical features and laboratory results at presentation in 48 children. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:30-6.

5. Hoover DL, Khan JA, Giangiacomo J. Pediatric ocular sarcoidosis. Surv Ophthalmol 1986;30:215-28.

6. Bodaghi B, Touitou V, Fardeau C, Chapelon C, LeHoang P. Ocular sarcoidosis. Presse Med 2012;41:e349-54.

7. Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular Sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med 2015;36:669-83. 8. Rothova A. Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:110-116.

Renuka Mopuru, MD,a Paulina Liberman, MD,a,b and Amde Selassie Shifera, MD, PhDa

aWilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA (former address)

bDepartamento de Oftalmología. Escuela de Medicina. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile (former address)