Amde Selassie Shifera, MD, PhD

Herein I present a case of CMV retinitis in patient whose only apparent risk factor for CMV infection was an advanced age. The patient was a 78-year-old man who presented with haze and floaters involving the right eye of about 11 days duration. About four weeks prior to his presentation he had noticed an erythematous rash that involved his right arm, left lower leg and back and that resolved three weeks later. His past ocular history was significant for cataract surgery with posterior chamber intraocular lens insertion in both eyes. His past medical history was significant for kidney cancer that was treated with nephrectomy 32 years prior to his presentation, hypertension and asthma. In addition, he had replacement of his aortic valve 8 years prior to his presentation.

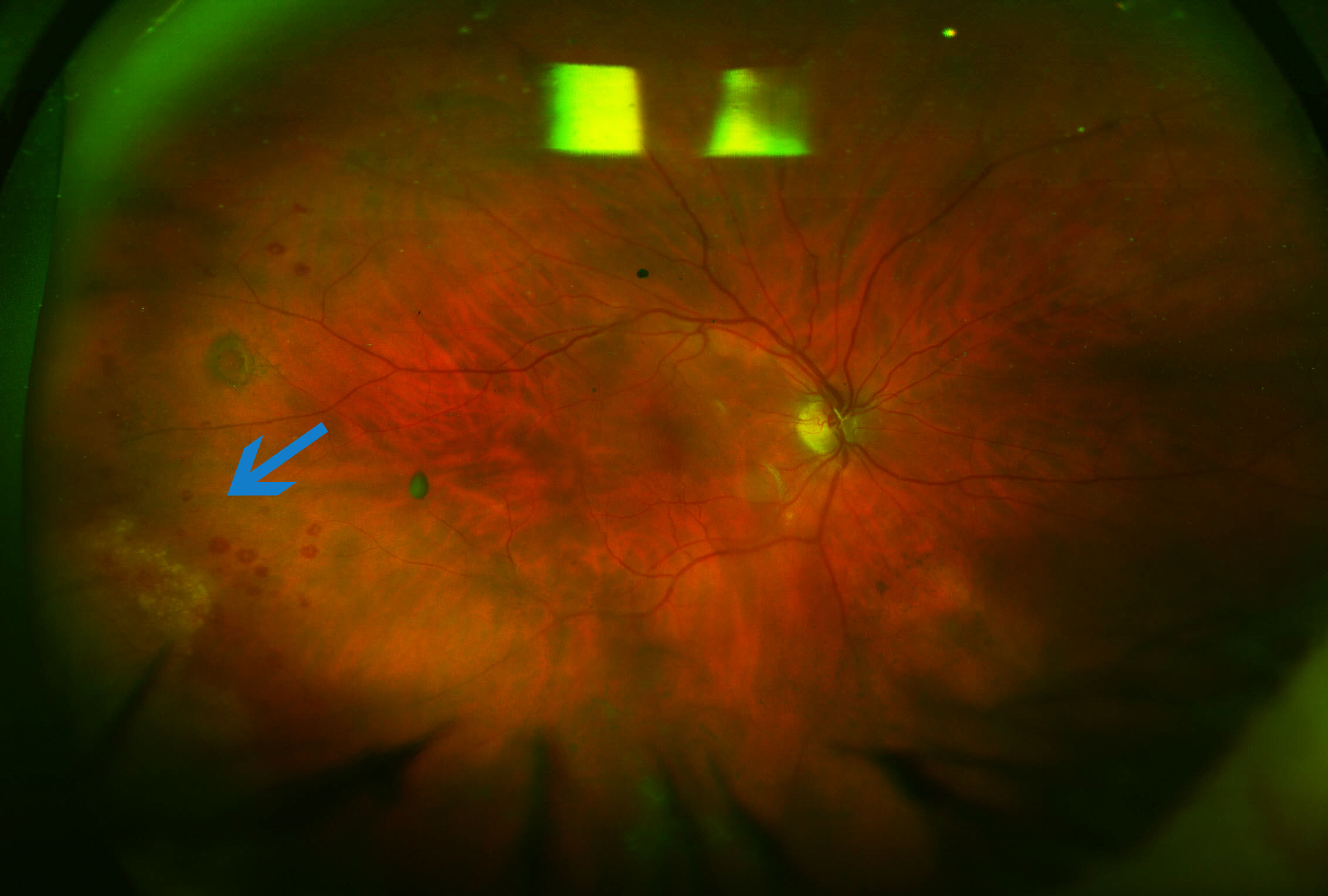

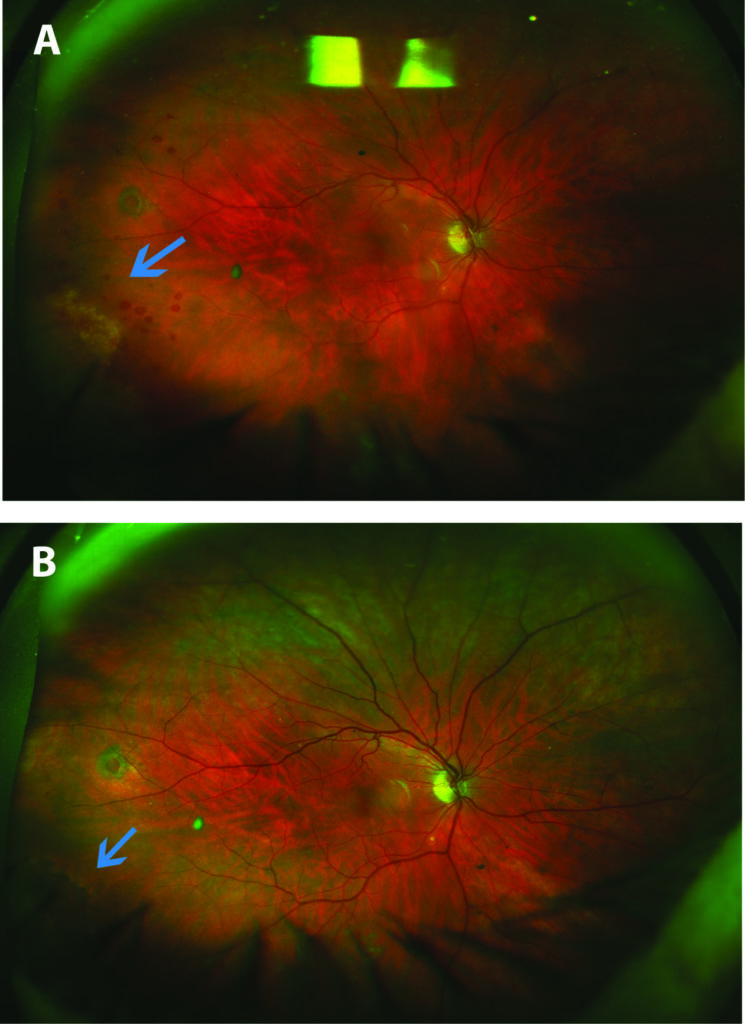

At presentation, his uncorrected visual acuity was 20/32 OD and 20/25 OS. There was no anterior chamber inflammation in either eye. In the right eye, he had trace vitreous cells and trace vitreous debris. In addition, there was a circumscribed area of granular retinal whitening in the peripheral retina inferotemporally with several intraretinal hemorrhages around the lesion (Fig. 1A). An incidental operculated retinal hole was noted in the right eye. There was no sign of inflammation in the vitreous or fundus of the left eye. PCR on aqueous obtained from the right eye was positive for CMV but was negative for herpes simplex and varicella zoster viruses. Serology was negative for syphilis and interferon gamma release assay for infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis was negative. The patient was positive for Toxoplasma gondii IgG antibodies but was negative for IgM antibodies. The patient was given a single intravitreal injection of 2.4 mg foscarnet in the right eye and was started on oral valganciclovir. Subsequently the presenting symptoms of the patient subsided and the intraretinal hemorrhages also resolved. In addition, the granular retinitis in the peripheral retina of the right eye became atrophic with no evidence of progression. The oral valganciclovir was discontinued after a total duration of five months. The retinitis remained inactive during follow up at two years after the initial presentation (Fig. 1B).

The patient had limited work up for immune deficiency including testing for HIV but no abnormality was found. The only risk factor for the development of CMV retinitis in this patient was his advanced age. The optimal treatment for CMV retinitis in a patient without HIV infection or with non-HIV causes of immune deficiency has not yet been well established but the typical regimen involves a combination of intravitreal and systemic anti-viral drugs. The duration of systemic treatment for CMV retinitis in such patients that has been reported ranges from 3 days (Jeon and Lee, 2015) to 11 months (Schneider et al., 2013).

References

Jeon S, Lee W K. Cytomegalovirus Retinitis in a Human Immunodeficiency Virus-negative Cohort: Long-term Management and Complications. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2015; (23): 392-399.

Schneider E W, Elner S G, van Kuijk F J, Goldberg N, Lieberman R M, Eliott D, Johnson M W. Chronic retinal necrosis: cytomegalovirus necrotizing retinitis associated with panretinal vasculopathy in non-HIV patients. Retina 2013; (33): 1791-1799.

Shapira Y, Mimouni M, Vishnevskia-Dai V. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV-negative patients – associated conditions, clinical presentation, diagnostic methods and treatment strategy. Acta Ophthalmol 2017.

Amde Selassie Shifera, MD, PhD

Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland (former address)